The Karate Kid and Masculinity

Last updated on March 8th, 2025 at 07:24 pm

Let’s talk about The Karate Kid – the original 1984 film that sparked a beloved franchise – and what it says about masculinity because that’s the thing I kept thinking about when I watched this film. I just watched this film for the first time, which is remarkable considering I’m in my 30s. But my husband loves this film and wanted me to watch it, so we did. In doing so, I discovered that The Karate Kid is an incredibly well-made, well-written film and an almost masterclass in setup and payoff. But beyond marveling at how the film is constructed, my most common thought as I was watching was, “Wow, this guy is going to beat his wife one day.” So, let’s talk about it.

(Let me preface everything with I have not seen Cobra Kai, so I have no idea how things develop for these characters in that show. We are dealing with the film itself.)

The boys/men in The Karate Kid

The boys and men in The Karate Kid are rough. They are mean and violent. Our introduction to Johnny is him stealing Ali’s radio and getting in her face. His friends cheer him on as he beats up Daniel with “no mercy” for the audacity of trying to defend Ali. Meanwhile, Daniel’s new friends abandon him for the crime of being beaten up because it goes against their understanding of how boys should behave (even though of course, none of them would have fared better).

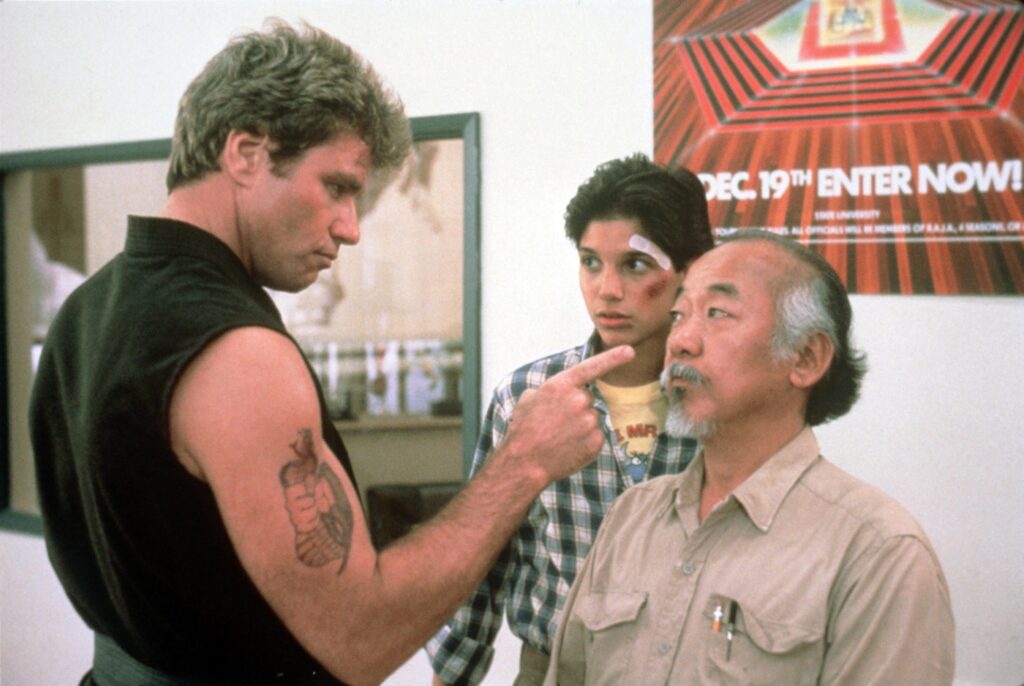

Throughout the film, Johnny is comfortable harassing and even sexually assaulting Ali. When Daniel sprays water on him, Johnny gets so violent that Mr. Miyagi has to physically step in to basically stop him from killing Daniel. Some of Johnny’s friends give a limp protest, but others egg him on.

The root at the bottom of this rotten tree is obviously John Kreese, the “no mercy” Karate instructor. He’s the one teaching this group of boys that compassion is bad, and they should be violent. Violence is the best method of solving their problems, obviously, and he’s succeeding in imbuing this world view into these boys. You see this clearly through his lessons and then their subsequent behavior throughout the film.

Mr. Miyagi is our foil for masculinity

I was not prepared for Mr. Miyagi’s backstory, and when it came up, I started crying, not just for him but for his wife. It was heart wrenching, especially as someone who is currently pregnant to imagine that situation, that incredibly real situation that I’m sure must have happened during Japanese internment. I’m not going to comment on any racism in The Karate Kid because I simply don’t feel informed enough to do so (I’m sure it’s there and worth talking about!), but I do think it’s interesting that a 1984 film was willing to talk about this so explicitly. Contemporary storytelling seems to forget about internment, and this 1984 film is just out here clearly highlighting its tragedy. And for my purposes, I’m interested in how this impacts Mr. Miyagi’s emotionality within the context of the film.

This is a man who could be hard, who could be angry. In fact, he has many legitimate reasons to be so, and I’m sure he must be at least a little. He’s also a man carrying a certain, inherent level of traditional, strong masculinity. He was in the military, he’s a skilled fighter, and he’s a handyman. He works with his hands and fixes things for a living.

However, he’s the main foil of the violent masculinity that we’re dealing with in the film. He’s the one who teaches Daniel to be a better man. He’s compassionate, has a strong sense of humor, does things for others just to be nice, and mourns his wife in a sincere way. His view of martial arts is for defense and protection and never for the sake of violence. The film might be full of violent masculinity, but it’s Mr. Miyagi, with his alternate views who the film says boys are supposed to like and emulate, which is fascinating. It’s not just that he provides an alternative way of living, but he’s presented as the correct way of living as a man.

How masculinity changes in the film

Here’s my potential hot take – Daniel and Johnny are quite similar in temperament, and the only things really separating them are class and Johnny being taken in by our “no mercy” Karate instructor first. They are fundamentally the same person being raised under much different circumstances. If Daniel had ended up being taken under the wing of the bad Karate instructor, he would probably be very similar to Johnny. Daniel gets lucky essentially.

So, at the beginning of the film, violence seems like the only answer. Daniel’s only hope to avoid being beaten by Johnny and his friends is further violence. He thinks he needs to impose his own violent masculinity. It’s Mr. Miyagi who comes in and shifts Daniel’s thinking and who encourages him to look at life in a new way, one that sees Daniel as neither victim nor aggressor.

It’s also the escalation of John Kreese, the other Karate instructor, at the tournament that starts to shift Johnny’s thinking. It’s a level of extremism that Johnny, faced with the alternative Daniel, struggles with, and it creates a crack in his certainty. Johnny’s shift does feel a bit contrived in the sense that I think he shifts a bit too much for realism, but we’re dealing with a film for teenagers, so I think that’s fine.

But really, this film is a demonstration of how the adults in our lives affect us and can shift our thinking in one direction or another. Mr. Miyagi’s patience and willingness to work with Daniel fundamentally changes his life and his view of masculinity for the better. The film shows how traditional masculinity can lead toward violence, especially toward and in regards to women. The treatment of Ali is clear in that. But it also shows how that violence can be opposed with compassion and feeling and create a stronger person for it.

The Karate Kid is an examination of masculinity and how it functions that I think is worth keeping.